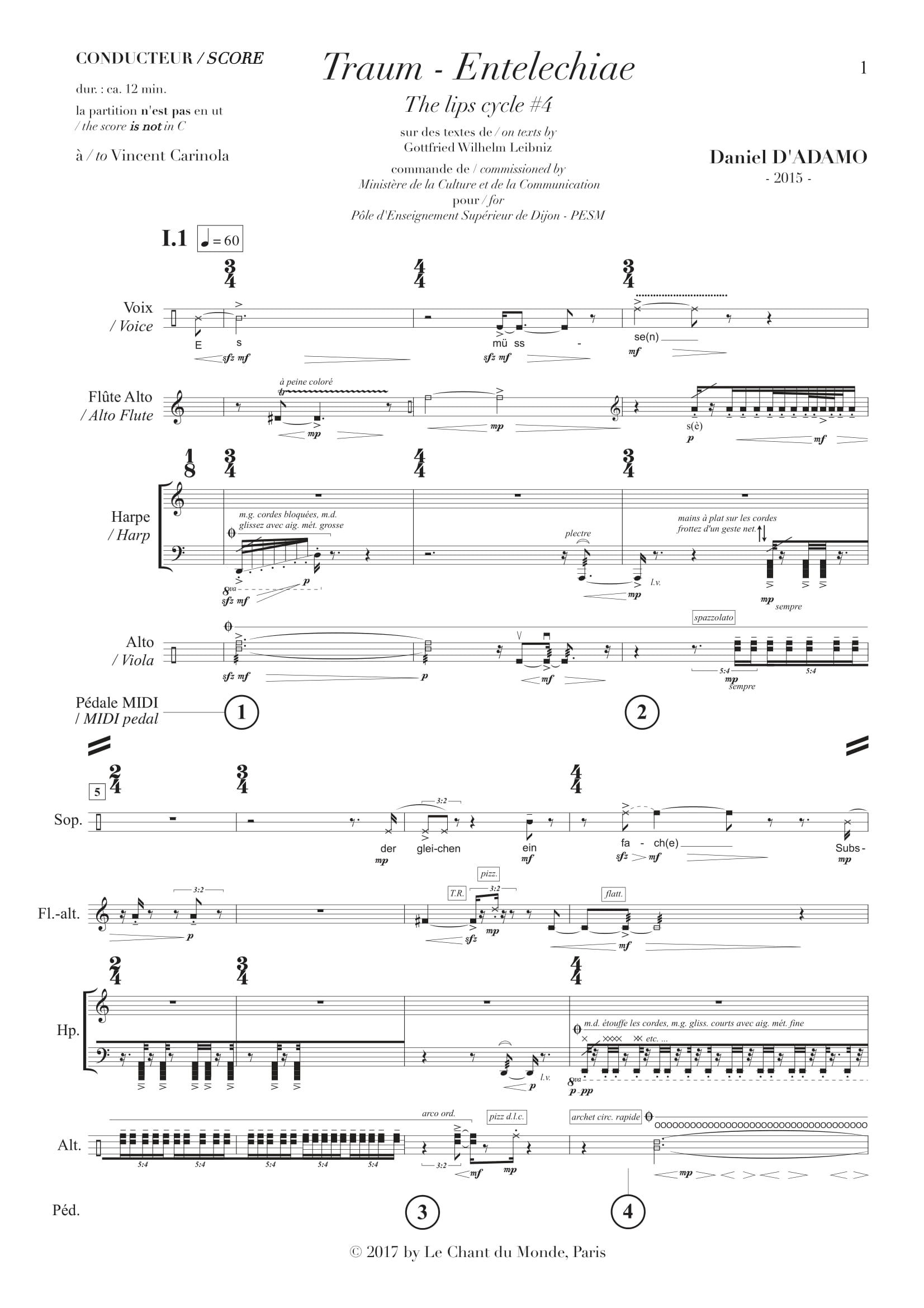

Publisher:

Premiere:

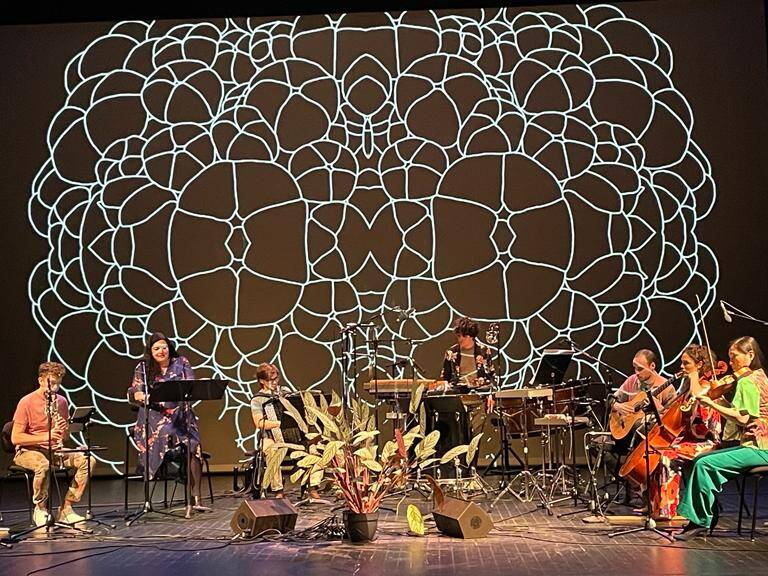

March 2016, Festival Why Note, Le Consortium, Dijon, France

Year of composition

2016

Commission:

Ministry of Culture, France

Duration:

12 min

Traum – Entelechiæ – (The lips cycle #4) – 2016

But a soul can read within itself only what is represented there distinctly; it could never bring out all at once everything that is folded into it, because its folds go on to infinity.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

I have read and re-read several times, in recent years, The Monadology of G. W. Leibniz. Fragment after fragment, his thought continues to develop his

reasoning through a series of concepts, some more mysterious but as fascinating as the others. They are the reflection, I think, of a way of perceiving and understanding the world: a mental mille-feuilles like the object of the study itself. Because the world is impossible to unfold totally: see as proof of the

vision of Leibniz the fact that we create ourselves here, at this very moment, one of the new (re)folds of the world. We do it through writing, performing and perceiving the music that has been composed and which is here interpreted and heard.

Like its title, Traum-Entelechiæ, alternates two very opposite musical and sound states: two entities that turn their backs. One succeeds the other as

beings who do not see or touch each other. But their proximity compels them to fold one towards the other, and in spite of themselves, they weave the

meanders that built-up the work.

I would have liked that, just like the world, the sounds constituting this piece, could also extend indefinitely.

Leibniz wrote La Monadologie originally in french to the intention of the Prince Eugene of Savoia, it is its translation to german by Henrich Koehler dated of 1720 that I preferred to use when composing Traum-Entelechiæ, the way this language naturally sounds corresponded better to my purposes.

Traum-Entelechiæ is the fourth piece constituting The lips cycle.

Daniel D’Adamo

Traum – Entelechiæ – (The lips cycle #4) – 2016

Mais une Ame ne peut lire en elle-même que ce qui y est représenté distinctement, elle ne saurait développer tout d’un coup tous ses replis, car ils vont à l’infini.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

J’ai lu et relu à plusieurs reprises, ces dernières années, La Monadologie de G. W. Leibniz. Fragment après fragment, sa pensée n’y cesse de développer son raisonnement à travers une série de concepts les uns plus mystérieux, mais aussi fascinants, que les autres. Ils sont le reflet, je pense, d’une manière de percevoir et de comprendre le monde: un mille- feuilles mental à l’image de l’objet même de l’étude. Car le monde est impossible à déplier totalement: voyez comme preuve de la vision de Leibniz le fait que nous créons nous-mêmes ici, en ce même instant, l’un des nouveaux (re)plis du monde. Nous le faisons à travers l’écriture, à travers le jeu et la perception de la musique qui a été composée et qui est ici interprétée et entendue.

A l’image de son titre, Traum-Entelechiæ alterne deux états musicaux et sonores bien opposés: deux entités qui se tournent le dos. L’une succède à l’autre comme des êtres qui ne se touchent ni ne se voient. Mais leur proximité les obligeant à un repliement de l’une vers l’autre ; elles tissent alors malgré elles les méandres qui font l’œuvre.

J’aurais voulu que, tout comme le monde, les sonorités constituant cette pièce, puissent elles aussi s’étendre indéfiniment. Leibniz a écrit La Monadologie originalement en français à l’intention du Prince Eugène de Savoie ; c’est sa traduction en allemand par Henrich Koehler datant de 1720 que j’ai préféré utiliser pour composer Traum-Entelechiæ, les sonorités propres à cette langue se prêtant mieux à mes propos.

Traum-Entelechiæ est la quatrième pièce constituant The lips cycle.

Daniel D’Adamo

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Monadologie, 1714 – Textauszug.

2. Es müssen dergleichen einfache Substanzen sein, weil composita vorhanden sind; denn das Zusammengesetzte ist nichts anders als eine Menge oder ein Aggregat von einfachen Substanzen.

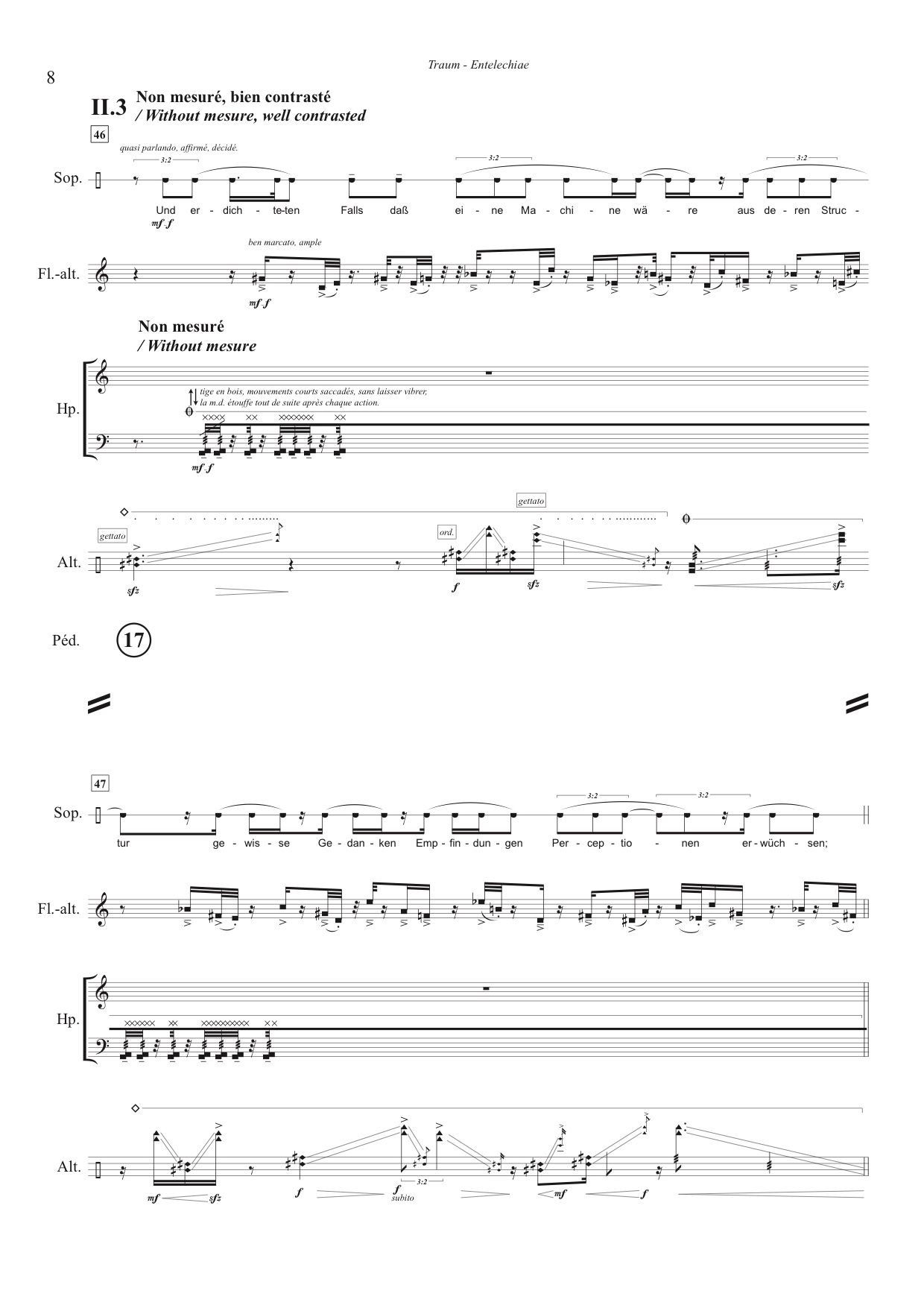

17. Man ist außerdem genötiget zu bekennen daß die perception und dasjenige was von ihr dependieret auf mechanische Weise das ist durch die Figuren und durch die Bewegungen nicht könne erkläret werden. Und erdichteten Falls daß eine Machine wäre aus deren Structur gewisse Gedanken Empfindungen Perceptionen erwüchsen; so wird man dieselbe denkende Machine sich concipieren können als wenn sie ins große nach einerlei darinnen beobachteter Proportion gebracht worden sei dergestalt daß man in dieselbe wie in eine Mühle zugehen vermögend wäre. (…)

20. Denn wir nehmen durch die Erfahrung bei uns selbst einen Zustand wahr worinnen wir uns keiner Sache erinnern und da wir gar keine deutliche perception oder Vorstellung haben welches z. e. geschiehet wenn wir in eine Ohnmacht sinken oder in einen sehr tiefen Schlaf verfallen darbei wir aber keinen Traum verspüren. (…)

5. Um eben dieser Ursache willen kann man keine Art und Weise begreifen / wie eine einfache Substanz natürlicher Weise einen Anfang nehmen könne; weil sie durch die Zusammensetzung oder Komposition nicht kann hervorgebracht werden.

—-

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, La Monadologie, 1714 – extraits.

2. Et il faut qu’il y ait des substances simples, puisqu’il y a des composés ; car le composé n’est autre chose qu’un amas ou aggregatum des simples.

17. On est obligé d’ailleurs de confesser que la Perception et ce qui en dépend, est inexplicable par des raisons mécaniques, c’est-à-dire par les figures et par les mouvements. Et feignant qu’il y ait une Machine, dont la structure fasse penser, sentir, avoir perception ; on pourra la concevoir agrandie en conservant les mêmes proportions, en sorte qu’on y puisse entrer, comme dans un moulin. Et cela posé, on ne trouvera en la visitant au-dedans, que des pièces, qui poussent les unes les autres, et jamais de quoi expliquer une perception. (…)

20. Car nous expérimentons en nous-mêmes un état, où nous ne nous souvenons de rien et n’avons aucune perception distinguée ; comme lorsque nous tombons en défaillance, ou quand nous sommes accablés d’un profond sommeil sans aucun songe. (…)

5. Par la même raison, il n’y a en aucune par laquelle une substance simple puisse commencer naturellement, puisqu’elle ne saurait être formée par composition.

—-

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, La Monadologie, 1714 – excerpts.

2. And there must be simple substances, since there are compounds; for a compound is nothing but a collection or aggregatum of simple things.

17. Moreover, it must be confessed that perception and that which depends upon it are inexplicable on mechanical grounds, that is to say, by means of figures and motions. And supposing there were a machine, so constructed as to think, feel, and have perception, it might be conceived as increased in size, while keeping the same proportions, so that one might go into it as into a mill. That being so, we should, on examining its interior, find only parts which work one upon another, and never anything by which to explain a perception (…).

20. For we experience in ourselves a condition in which we remember nothing and have no distinguishable perception; as when we fall into a swoon or when we are overcome with a profound dreamless sleep (…).

5. For the same reason, there is no conceivable way in which a simple substance can come into being by natural means, since it cannot be formed by composition.

—-